Anton Codelli: The Baron Who Bridged Continents

Driven by imperial ambition, a brilliant engineer from Ljubljana built a groundbreaking wireless communication station in colonial Togo, only for it to be destroyed in the chaos of World War I.

In the early summer of 1914, as the world teetered on the brink of the First World War, a momentous technological achievement was taking shape in the heart of Togo, a German colony in Africa. After years of challenging construction, led by the brilliant engineer Anton Codelli, one of the most advanced and powerful radio stations of its time became operational.

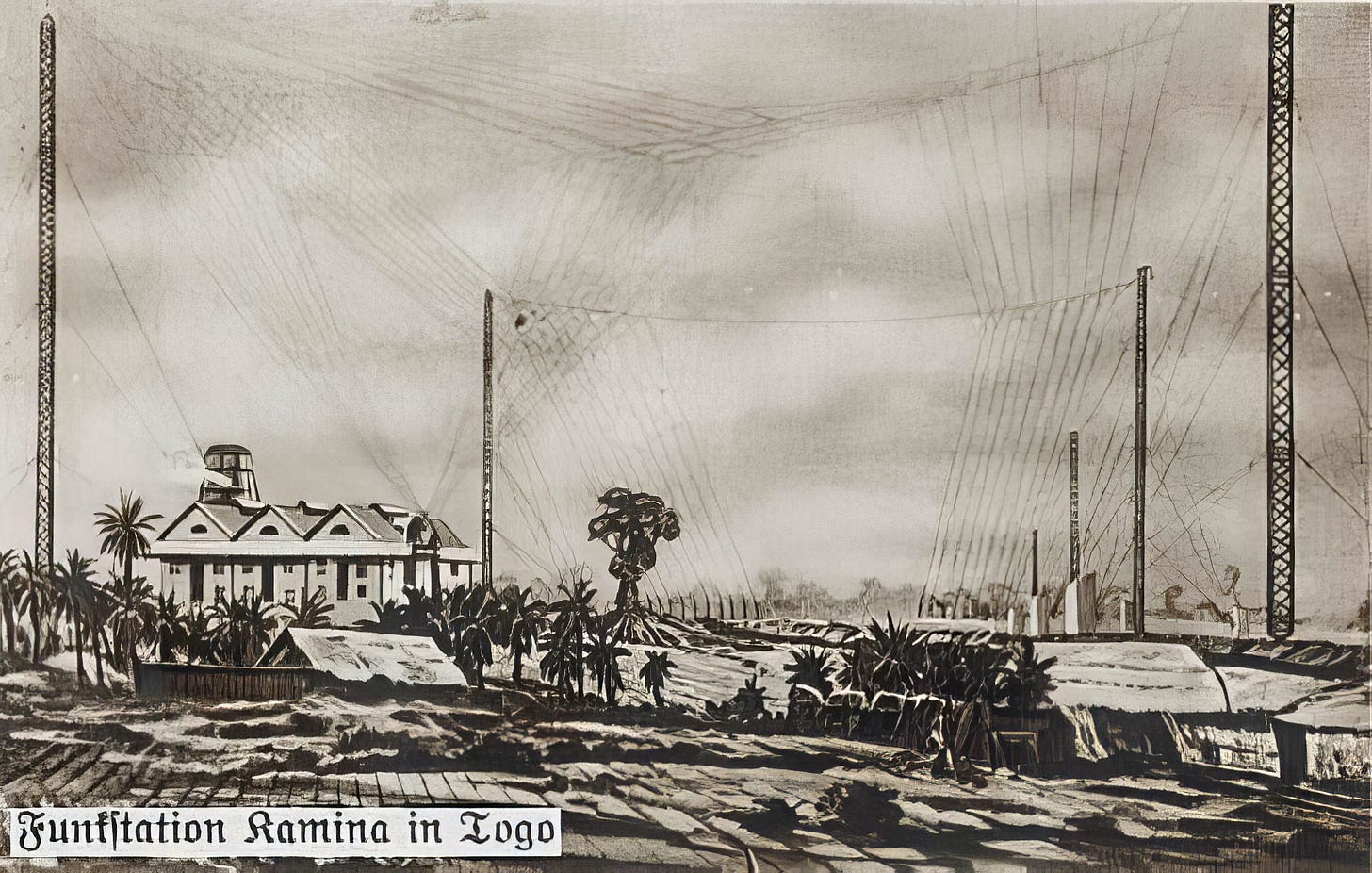

This ambitious project, spanning kilometers and incorporating a power plant, living quarters, and administrative buildings, was not merely a marvel of engineering but also a strategic asset for the German Empire, designed to establish a global communication network independent of rival powers. With its colossal wire antenna supported by towering iron masts and massive concrete blocks, the station could transmit signals over 5,000 kilometers to Berlin and beyond, connecting other colonies and ships at sea.

On the eve of war, as tensions simmered between European powers, the race for global dominance extended beyond territories and resources to a new frontier: communication. At its core was a revolutionary technology—wireless telegraphy. Determined to challenge Britain's dominance through its vast undersea cable network, Germany embarked on a bold endeavor: the construction of the transcontinental Kamina radio station in its West African colony. This station was not only a technological marvel but also a symbol of Germany's aspirations for global power and its commitment to modernizing its colonial reach.

Rising from the dusty savanna, Kamina embodied Germany’s vision of global connectivity and its ambitions to project influence far and wide. Entrusted with this groundbreaking project was Anton Codelli, a baron from Ljubljana whose aristocratic heritage was matched by his engineering genius. Selected by the renowned German company Telefunken, Codelli took on the challenge of transforming an isolated colony into a hub of technological advancement.

Building Kamina Station in Togo

Between 1911 and 1914, Kamina’s construction in Togo—a remote colony in West Africa—posed monumental challenges that tested the limits of early 20th-century engineering and logistics. Harsh climates, rugged terrain, and the absence of supporting infrastructure required meticulous planning and ingenuity. Materials and prefabricated components were shipped from Germany and assembled on-site, overcoming significant logistical hurdles.

The strategic choice of Togo reflected Germany’s broader aspirations. Positioned as a central hub, Togo allowed Kamina to link Berlin with other German colonies and naval operations, integrating colonial outposts into a unified network. This vision of seamless communication underscored Germany’s imperial ambitions, enhancing military coordination and administrative efficiency across its territories.

Known for his innovative spirit, Anton Codelli transformed this isolated colony into a hub of technological advancement. Under his direction, Kamina emerged as a marvel of modern engineering, its towering masts and advanced transmitters symbolizing the dawn of global connectivity. Codelli’s leadership, combining scientific precision with creative problem-solving, was instrumental in overcoming logistical and technical challenges.

The station's scale was staggering. Anchored by reinforced concrete blocks, massive antenna masts were designed to withstand Togo’s intense weather conditions, including heavy rains and fierce winds. Advanced transmitters and receivers operated with unparalleled range and efficiency, making Kamina a vital node in Germany’s global communication strategy. The facility also included a centralized power plant, administrative buildings, and living quarters, meticulously planned to ensure functionality and support personnel.

However, Kamina’s construction was not without controversy. The use of forced labor, common in colonial projects, highlighted the exploitative practices of the era. Local workers endured grueling conditions, juxtaposed with the advanced technological infrastructure they helped create. Although Codelli reportedly treated laborers better than was typical for the time, the project remained a stark symbol of the inequities of colonial rule.

By mid-1914, Kamina stood completed—a towering testament to human ambition and ingenuity. Yet, as the shadow of war loomed, Kamina’s moment of triumph would be short-lived. The turbulence of World War I would soon challenge the resilience of both the station and the empire that built it.

Anton Codelli: The Baron from Ljubljana

Anton Codelli (1875-1954) was far more than just a nobleman with a fancy title (though he certainly had that - Anton Freiherr Codelli von Codellisberg, Sterngreif und Fahnenfeld!). He was a restless spirit, a born inventor who defied expectations and left his mark on everything from cars to communication.

Born in Naples to an aristocratic family with roots deep in Slovenian history, Codelli could have easily settled into a life of privilege. He spent his youth between Ljubljana and Vienna, attending the elite Theresianum boarding school, a breeding ground for future emperors and diplomats. But while his classmates pursued law or politics, Codelli was captivated by the burgeoning world of technology.

This fascination led him down an unconventional path. After a brief, unsatisfying stint in the Austro-Hungarian navy, he abandoned his law studies in Vienna to pursue engineering. This was a bold move for a young baron, a rejection of the traditional roles expected of his class. It spoke to his independent spirit and his drive to forge his own destiny.

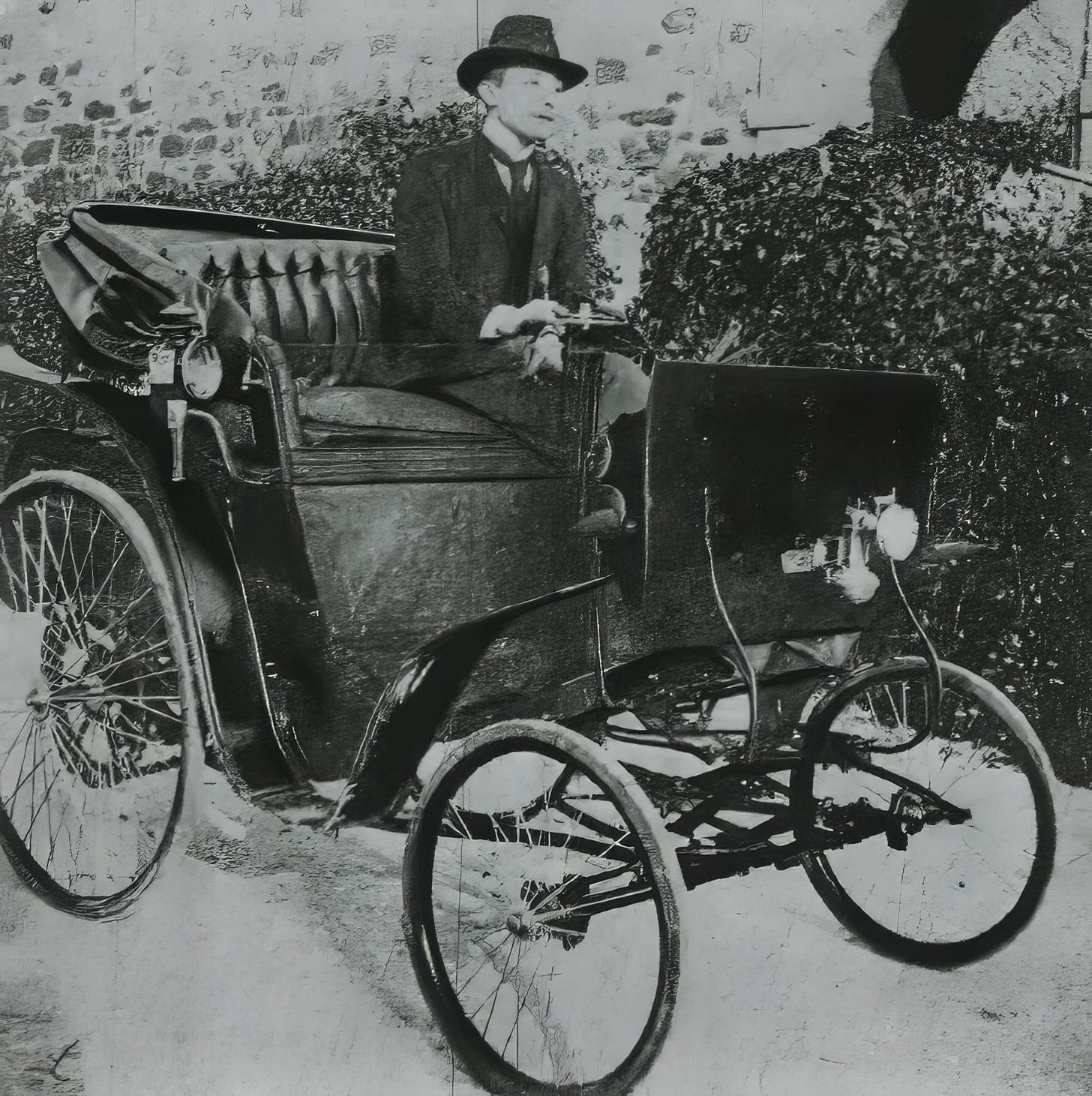

Codelli's interests were as diverse as his talents. He is perhaps best known for bringing the first automobile to Ljubljana in 1898, a feat that earned him both admiration and suspicion. In the sleepy provincial town, Codelli's "devil's wagon" was initially met with fear and disapproval, as people were unnerved by its speed of around 20 km/h. But his true passion lay in pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

Around the turn of the century, he became captivated by the magic of radio. Collaborating with physicist Albin Belar, he built Ljubljana's first radio receiver, a device that could capture time signals broadcast from afar. He then turned his attention to the sea, developing a radiotelegraph system for the Austro-Hungarian navy, enabling ships in the Adriatic to communicate directly with command centers on the coast.

These early successes cemented Codelli's reputation as a gifted innovator. In 1911, his talents caught the eye of Telefunken, a leading German telecommunications company. They offered him a challenge that would define his legacy: to establish a long-wave radio link between Berlin and Togo, a German colony in Africa. This ambitious project, the Kamina radio station, would become a testament to Codelli's vision and engineering prowess.

Kamina in Operation

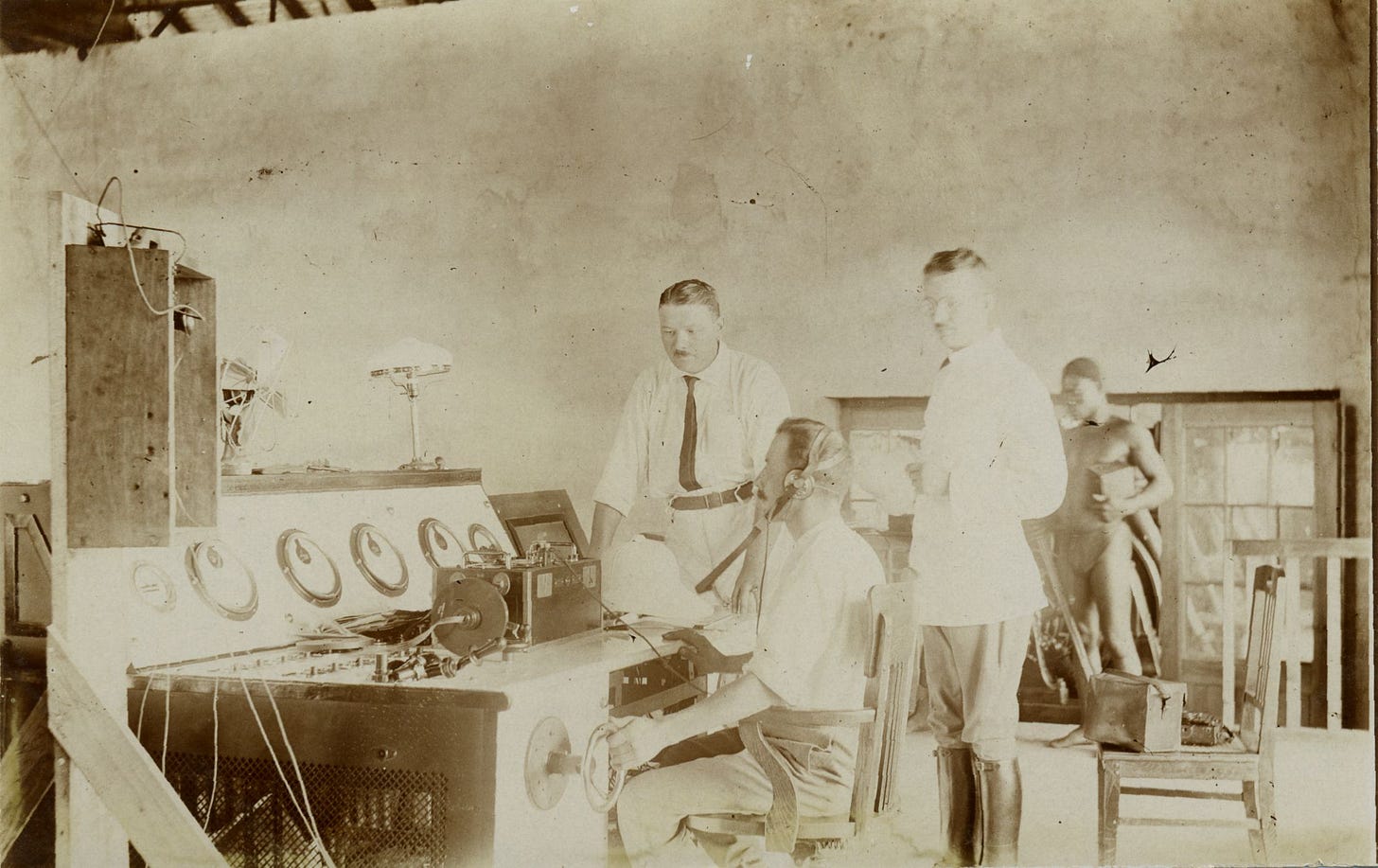

When Kamina became operational in 1914, it immediately demonstrated its groundbreaking capabilities. The station’s advanced wireless technology enabled transcontinental communication on an unprecedented scale. Messages were transmitted seamlessly between Berlin and Togo, traversing over 5,000 kilometers, while additional links connected Kamina to other German colonies and naval fleets stationed in distant seas.

The heart of Kamina’s operation was its massive transmitter system, powered by a cutting-edge generator capable of producing enough energy to drive the powerful signals. The station’s towering iron masts supported a complex web of antennas, which radiated messages across vast distances. Operators worked in meticulously designed control rooms, utilizing state-of-the-art equipment to ensure the clarity and reliability of transmissions.

Kamina played a dual role in communication. Militarily, it was a vital link for Germany’s colonial and naval operations. In the early days of World War I, the station transmitted critical strategic information between the German High Command and its forces in Africa and the Atlantic. Its ability to maintain uninterrupted communication offered a significant advantage, enabling swift coordination of military resources across vast territories.

On the civilian front, Kamina served as a hub for administrative communication, facilitating governance and trade within the German Empire’s colonial network. The station’s efficiency in relaying messages significantly reduced the time required for decisions and responses, streamlining colonial administration and reinforcing the integration of outposts into the broader imperial framework. In total, the station managed to transmit 229 messages between Germany and its colonies before it was demolished.

The Destruction of the Kamina Radio Station

The outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914 drastically altered the fate of the Kamina radio station. Initially envisioned as a critical hub for Germany's transcontinental communication network, Kamina's strategic importance made it a prime target as Allied forces advanced into Togo. The station, which had only recently become operational, found itself at the center of a broader struggle for control over global communication infrastructure.

The destruction of the Kamina radio station was a dramatic and controversial episode in the early months of World War I. Faced with the rapid advance of British and French forces into Togo, German authorities stationed at Kamina were ordered to ensure that this state-of-the-art facility would not fall into enemy hands. On August 24, 1914, after intense deliberation and following direct instructions from Berlin, the German garrison began the systematic dismantling and destruction of the station. Massive antenna masts were toppled, transmitters were dismantled, and key components of the sophisticated equipment were destroyed beyond repair. The operation was overseen by German officers, who understood both the strategic necessity and the symbolic loss that this act entailed.

The decision sparked controversy both within Germany and among observers. While military leaders argued that destroying Kamina was essential to deny the Allies a significant communication advantage, others lamented the obliteration of a facility that represented the pinnacle of technological progress and engineering achievement. Local populations, who had been involved in the station's construction and maintenance, watched as the massive infrastructure was reduced to ruins, leaving behind a mix of awe and despair.

Globally, the destruction of Kamina highlighted the vulnerability of technological assets in times of conflict. It underscored the critical role that communication networks played in modern warfare and foreshadowed the increasing militarization of technology in the 20th century. Despite its brief operational lifespan, Kamina's legacy endures as a testament to the transformative potential of wireless communication and its profound impact on geopolitics.

A Legacy in Ruins

The Kamina radio station, though short-lived, left a profound legacy on the development of global communication technologies. It served as a prototype for transcontinental wireless communication systems, demonstrating the feasibility of transmitting messages across vast distances without reliance on physical cables. This innovation laid the groundwork for the evolution of radio communication, shaping advancements in global connectivity that echo into the present day. In many ways, Kamina was a precursor to the satellite networks and fiber-optic systems that now underpin modern telecommunications.

In Togo, the remnants of Kamina hold cultural and historical significance. The site has become a symbol of the complexities of colonial history, representing both the technological advancements brought by German imperialism and the exploitative labor systems that made such projects possible. For the local population, Kamina's story is a reminder of the intertwined narratives of progress and oppression that define much of colonial history.

Anton Codelli’s role in this story elevates him as a visionary in the broader narrative of technological pioneers. His ability to transform an isolated West African colony into a hub of groundbreaking communication technology highlights his exceptional engineering talent and foresight. Codelli’s work, though deeply rooted in the context of its time, resonates as a precursor to the globalized and interconnected world we inhabit today.